Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players, by Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., and Harwood, C. Journal of Sports Sciences, November 2012; 30(15): 1593–1604

Quick name drop here. The authors note that this study is building on, in part, one of the first studies looking at aspects of player development done by Nick Holt and John Dunn, both of whom I had the pleasure of taking classes from in University. They made sport psych cool. In short, they came up with a model that the major competencies that contributed to successfully transitioning to being a professional soccer player was discipline, commitment, and resilience, all of which is coupled with favourable social support.

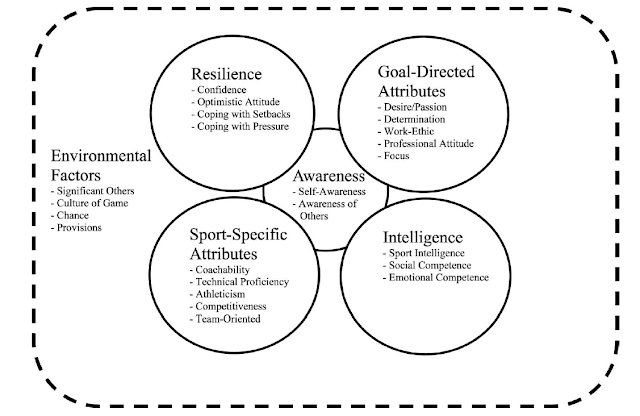

The purpose of the present study was to build upon identifying the major factors, but from the perspective of expert coaches in the British FA system. I'll let the resultant chart do much of the talking:

|

| Figure 1 from Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., and Harwood, C. Journal of Sports Sciences, November 2012; 30(15): 1593-1604 |

I think many of these are fairly self-explanatory, and make quite a bit of sense. Rather than go into detail, why don't we find out what conclusions the authors came up with? Most notably, their unique insight is regarding how "awareness" is the "fundamental agent of change that drives effective development".

More specifically "the coaches felt it was imperative for young players to understand that adversity can facilitate development ... adversities were largely perceived as 'opportunities to grow' where by players must introspectively 'dig deep' to evolve ... the capacity to consciously reflect, assimilate and adapt was considered a key determinant in effectively translating one's potential into excellence" (page 1601).

Also it should be noted how "environmental factors" are an overarching factor. These are wide-ranging factors that often most notably include non-selection to a team and injury (which is an extensive sport psych topic in itself for another time!)

So, what does this have to do with orienteering?

I think that you could take cross out football, and put in orienteering. Its really that simple. Of all the aspects of the entire above chart, the only one I can think of that may not apply to orienteering are the "team-oriented" sport-specific attribute, since its not a team sport. But that's what make that section sport-specific?

In particular, I would argue that "resilience" is far more prevalent in individual sports, and even moreso in orienteering. In individual sport, you will lose. And you will lose a lot. Even the best in the world probably lose more often than not. The big question is whether you can take each loss as a way of being better for next time. More specifically, orienteering is the classic sport of dealing with adversity. The sport is built around agreeing to having adversity handed to you on a piece of paper. The way you handle that adversity directly affects your own outcome. When referring to self-awareness, the authors quoted once coach who said:

"The biggest thing for me about development is how young players experience disappointments. How did they feel in that game? Did they lose self control? Did they lose focus? Did they lose confidence? Next time that happens, how can I handle that better?"

Doesn't that sound awful relevant to orienteering? Do you do that after every disappointment?

|

| Admittedly, in this case, the only thing that could have been done better is not having such a stupid timing system. |

So what could those developing young orienteers take from this chart? I think in planning, it needs to be asked whether our plans encompass the many traits that apply to athlete development? What does a particular camp focus on? Unfortunately every athlete is different, so no one strategy will be assured to work for everyone. My impression has been that our country's approach has lacked a focus on athleticism and competitiveness, instead of focusing on technical proficiency, and leaving the former to each individual's athlete's devices. Its no wonder that there have been several highly successful orienteers that have transitioned from other endurances sports into orienteering - the athleticism aspect has been very strongly ingrained.

In the end, I'm not sure its possible to be more specific than extremely vague. One could spend pages upon pages theorizing different ways to develop each individual factor above in the context of orienteering, and it perhaps should even come to that. As the authors state:

"Nonetheless, we contend that a favourable combination of the factors identified in this study would serve to enhance a young player’s likelihood of successfully transitioning to the professional level."

So.... that's a lot of factors. What do you think you are lacking? Can you theorize how that might have been better developed?

And one day, with enough training, you may be as successful as this guy: